Time Warp – The Experience of Time and Social Care - Jess Thom

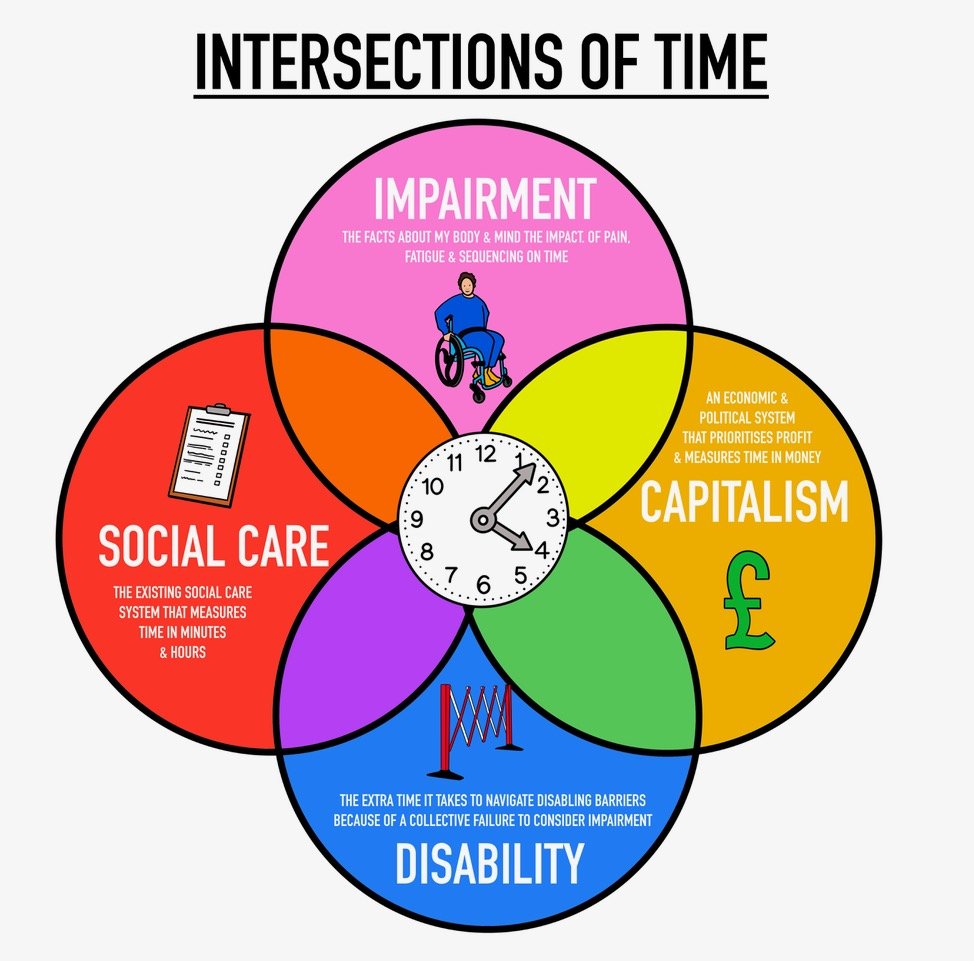

Intersections by Jess Thom, 2024

How long does it take you to go to the toilet?

What about eating dinner?

How many times a week can you ‘access your community’?

You can’t just say ‘it depends’, which it obviously does. If you had to put numbers on these things, what would they be?

Questions like this will be all too familiar to anyone who, like me, draws on social care or has a family member who does. These questions are just the beginning of the complex way in which disability, impairment, care and capitalism intersect and impact our experiences of time.

I need support to live and work. When I talk about support, I mean the help I need from other people 24 hours a day. It’s what I need to be safe, do the job I love, make plans, be spontaneous, have a pet, go for a swim, and be an aunty.

I’m lucky to have a support plan that meets my requirements, something that hasn’t always been the case and isn’t true for many disabled people and elders. My support is funded from different places, including social services, the NHS and Access to Work. Each funder reviews their contribution annually, a process that means my care is under almost constant scrutiny. Of course, support needs to be reviewed and monitored but little thought is given to how this effects those of us whose lives are built on social care. Or how narratives around Austerity, productivity and value, effect how precarious our lives can feel.

My care is broken down in intense detail and every minute of activity is a battle. For example, I’ve had a social worker tell me that 45 minutes is too long for help preparing and eating an evening meal and ask if I really need to ‘access my community’ (AKA leave the house) every weekend.

Accumulatively this process has deeply affected my relationship with time. I never just think about my own time, I think about the time of those supporting me, about who’s paying for what, and about what time has been claimed for or reported on.

Getting support hours agreed is a tiny part of the never-ending obstacle course that is Independent Living. Finding people to take on those hours is currently a huge issue for many disabled people, because there’s an ongoing shortage of personal assistants and carers.

A week ago, I sat in the bath sobbing, frantically messaging PAs, friends and even neighbours, desperate to find someone who could be with me the following day. I got it sorted within a couple of hours, but it took me days to recover from the panic and pressure of this close call.

Without the right support my world shrinks very quickly, and time expands, so even short periods alone feel like dangerous voids. The threat of unsupported time is constantly present in my life, and I expend huge amounts of time and energy managing my support to avoiding being on my own.

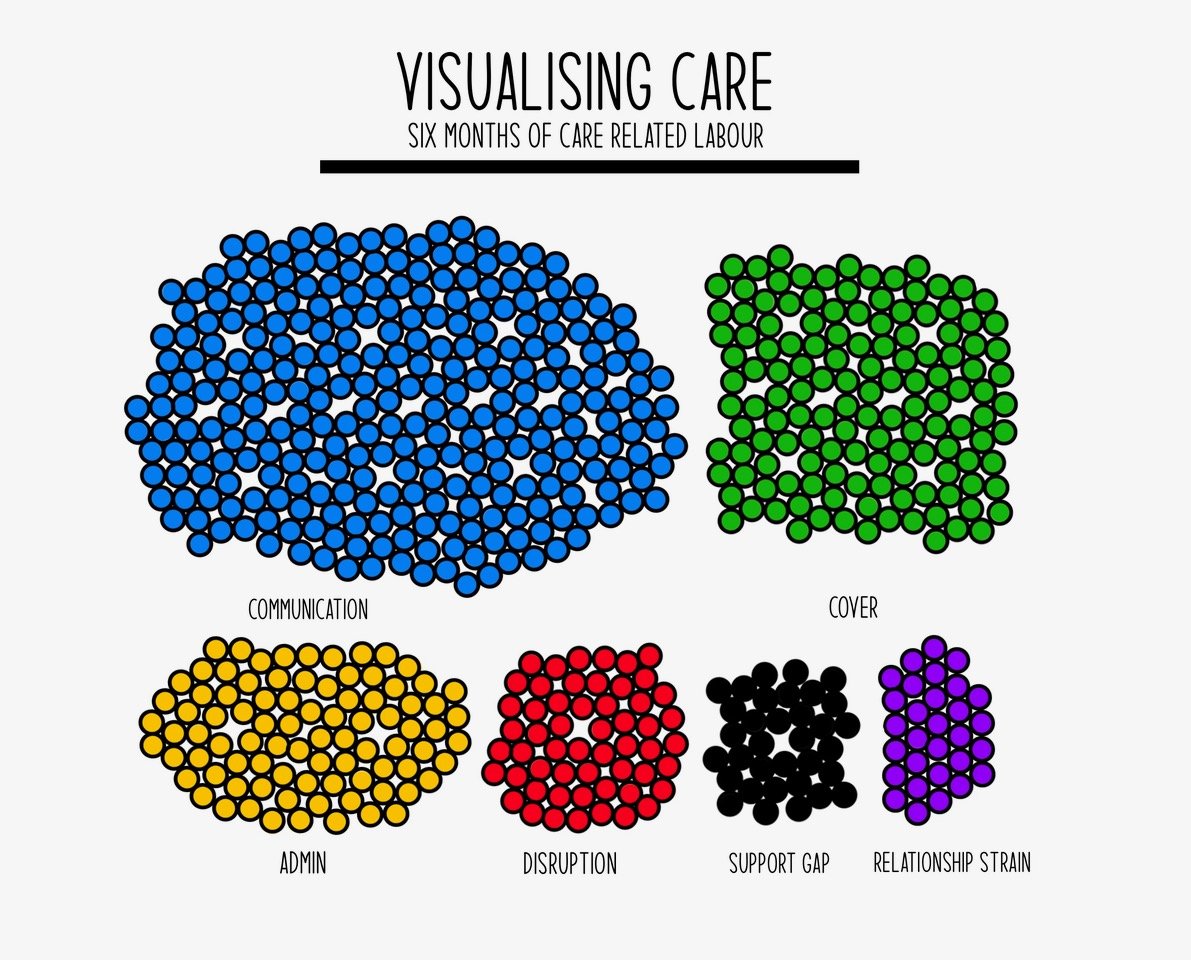

In April 2023 I started tracking the hours I spend organising care, and I’ve used this data to create images that make this process visible.

Visualising Care by Jess Thom, 2024

While these images show the time I take communicating with PAs, or processing payroll, or reporting to my council, they don’t reflect the emotional labour involved. As I write this for example, I’m also worrying about a support gap tomorrow night and about who’s going to cover one support worker who’s having an operation later this month. I’m also having a WhatsApp conversation with my sister to negotiate what time she can support me. I’ve also been thinking about the shed load of annual leave I’ve got left, which builds due to of the complexities and extra costs of holidays when you need 24 hour support.

My time is always fragile, whether that’s because of my body, brain, energy, or pain, or because of a lack of support.

“Time and care are a dance, sometimes we’re in sync and it’s beautiful, at other moments it’s more of a brawl.”

There are some organisations challenging assumptions around time within care in interesting ways, for instance Stay Up Late's 'No Bedtimes' campaign that challenges the inflexible systems that prevent many social care users from socialising. Or Social Care Future’s work on ‘changing the story’ of social care, so that its power and potential are perceived more clearly.

What every social work assessment, invasive question, and last-minute cancelation has given me is a nuanced appreciation of time and a deep understanding of the importance of having agency over it.

Time within social care is rarely allowed to flow – minutes are measured, hours are checked, gaps in support stretch and contract with little warning. Time and care are a dance, sometimes we’re in sync and it’s beautiful, at other moments it’s more of a brawl.